The Productivity Gap in the UK Isn’t a Puzzle; We Just Aren’t Doing Anything About It

January 7, 2024

My entry to the TxP Progress prize, a blog prize that has invited answers to the question: “Britain is stuck. How do we get it moving again?”

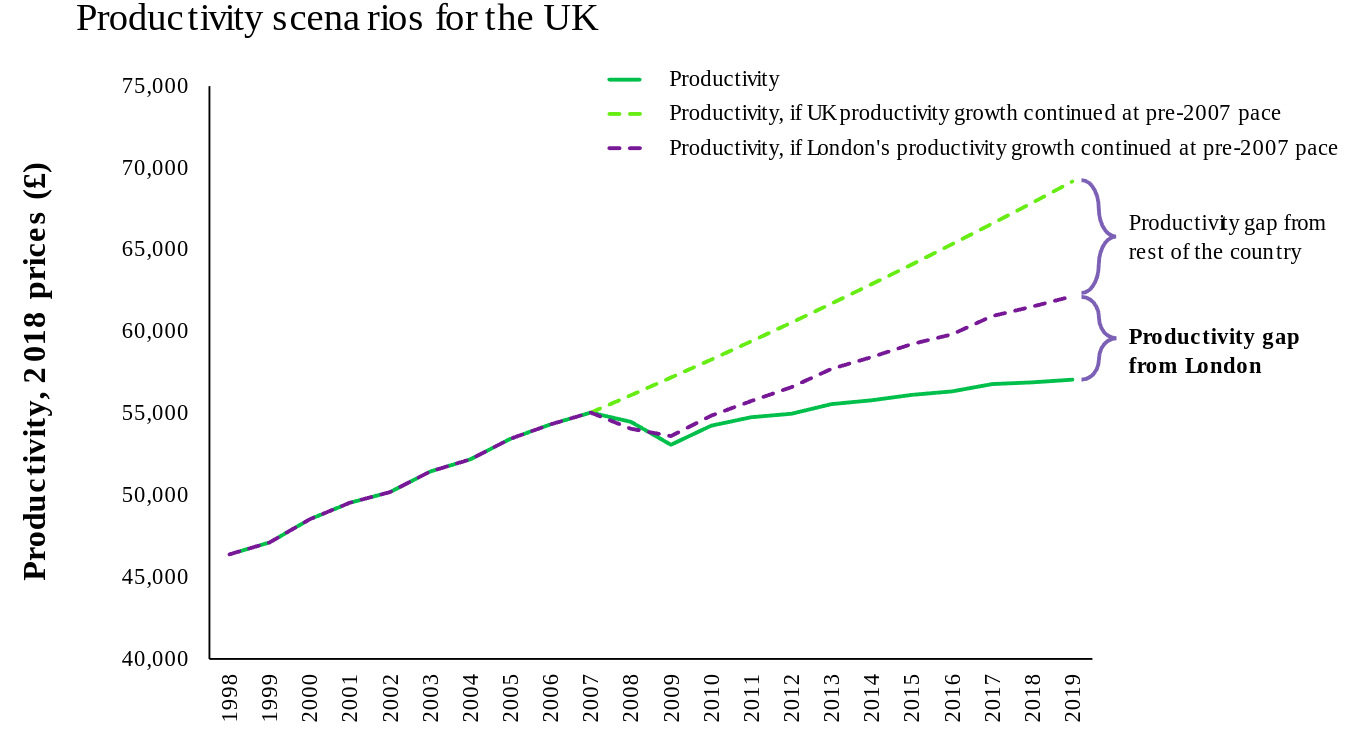

Britain has great strengths, but for the majority of my life it has been in a period of economic stagnation. Real wages increased up to 2007, where beyond then they have plateaued. At the same time, the UK’s productivity gap with France, Germany, and the US has doubled to 18 per cent, costing us £3,400/year in lost output per person. We’ve missed out on a lot over the last 15 years.

Constrained by labour supply and demographic shifts, such as ageing population, it’s clear that if we are to kickstart future growth it will need to come from improving our productivity to keep pace with historical rates of GDP growth.

Source: Centre for Cities

Source: Centre for Cities

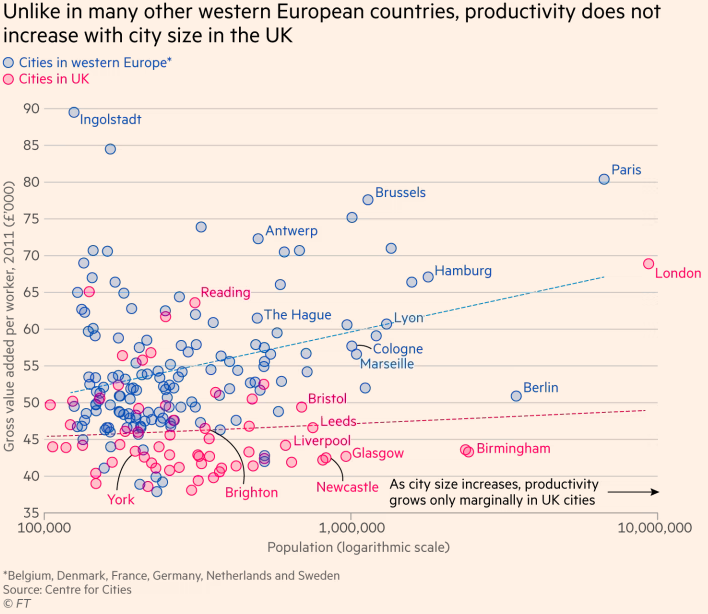

The UK is the second biggest services exporter in the world and 80% of economy is in its cities. We begin by focussing on the most obvious city, London. The capital is a global economic hub and contributes significantly to the UK’s overall GDP (about 22%). It also enjoys higher levels of productivity - around 40% higher than for the UK as a whole. One of the primary drivers for this increased productivity is likely due to the benefits of agglomeration: The bigger a city becomes; the more productive it is. This is observed across Europe, where strong positive correlations in population and productivity are clearly observed.

The UK is markedly unique in that when we exclude London, these benefits are barely observed when we look at our own cities. If anything, the larger a city becomes, the less productive, and the poorer it is.

This graph provides evidence that prioritising London at every opportunity has come at a cost. Maximising the potential of London while minimising the cities everywhere else might have worked for us in the past - but I would argue that in our services-dominated economy of the present, something is going very wrong with what we’re doing with our cities.

Through most of the 20th century, the disparity in GDP per capita among UK regions, while present, remained comparatively modest within the European context. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, regional economic inequality started to escalate across various industrialised economies (IMF 2019). Regional inequality exists across the world, but it’s the UK that stands out for the extent to which this trend unfolded. By the 2010s, the country had emerged as one of the most regionally unequal (a leader when you look at the top 25 OECD countries), encompassing disparities in GDP per capita, productivity, and disposable income.

Many countries have regional differences in productivity, but for a country so densely populated, our inequality is striking. IPPR’s State of the North 2019 report stated that ‘the UK is more regionally divided than any comparable advanced economy’.

We’ve centralised our economy so much in one place and it’s been letting us down for a while now. London contributes 41% of the productivity gap when compared to the pre-2007 pace. We’re seeing that despite a leading finance sector, London is harming the rest of the country’s economy. We can see that London has made the North of England’s economy not as large as it could be, as disproportionate investment towards London hinders the North’s ability to diversify and compete.

Whatever we need to do to solve Britain’s economics problem relates to what we do with our cities. And as most major cities in the UK are found in the North of England - a product of our industrial past - this becomes yet again a discussion about the North-South divide.

You’ve heard it before: ‘levelling-up’, ‘devolution’, ‘north-south divide’, ‘Northern Powerhouse’ and now ‘Network North’. We know full well we need to invest in areas outside of London and the south-east in order to fix things.

The Northern Powerhouse exists as an initiative because the government can see that the North is not as economically strong as it could be. There have been recent waves of devolution across the country since 2011, with increased recognition being placed on the importance of big cities in driving economic growth.

But despite this, Britain has become even more fiscally centralised since 2015. This has happened because despite all of the promises to bridge the regional productivity gap, for all the talk of levelling up, devolution, Northern Powerhouse, Network North - investment has not materialised and most attempts to inject funding are failures.

The political language is identical to that of fifty years ago, because so, too, are the underlying conditions. The only progress has been to further widen the divide to be far worse than it was before.

There is a lack of political will despite what’s staring us in the face: We have a prime minister proudly proclaiming a redirection of funds away from economically disadvantaged urban regions. The much-needed additional capacity for northern train infrastructure is presented enticingly like a dangling carrot, only to be withdrawn, leaving the East Coast Main Line forced to make choices between passengers and freight. This approach appears designed to prevent any possibility of ‘levelling up’ the North.

It’s easy to be pessimistic, but only because we’ve never even tried to fix this.

It feels like the last 10 years of government’s levelling up agenda has been little more than a rehearsed soliloquy - a performative dance that fails to break the shackles chaining cities to a legacy of neglect. It’s not just about glossy words; it’s about the substance of action, the grit of investment, the commitment to rewriting the verses of economic injustice. Yet, we’re left with a crescendo of broken promises. We are not putting in our best efforts towards changing our future, and we are just pretending otherwise if we claim we are.

The task for this blog is to provide a solutionist approach to fixing Britain’s economic malaise. But as I remain convinced that the fundamental blocker to UK’s progress lies in the poor structure and design of Britain’s cities, it’s difficult to imagine a future where we cement ourselves as global leaders in renewable energy, or machine learning, without every step taken inhibited by the baked-in productivity gap.

The way we address regional inequality can be exciting and technocratic and solutionist. Here’s what I would do:

- Poor connectivity limits the effective size of city regions. That’s why fixing transport is so obvious and important. If you earmark money for this purpose, don’t then spend it fixing potholes in London.

- Reexamine devolution through an economic lens, and be even more ambitious. Comprehensively devolve transport, housing, and digital infrastructure to local government.

- There is a misallocation of government research and development funding, preferenced towards London despite other areas having better returns. If we properly distribute spending across our core cities, increased business investment will follow.

- Start our projects in the North, rather than starting in London. Do this as a matter of principle. Actually mean it when we say we will invest in levelling up.

- In the UK we have a long tailed distribution of low productivity SMEs, propped up by a few high performers. Fix the business ecosystem by allowing different types of companies to thrive elsewhere than London and the South East. Introduce tax incentives and grants for tech companies and startups setting up outside of London.

- Establish regional development funds to support innovation and entrepreneurship. Encourage the growth of industry clusters and innovation hubs in key cities, with an emphasis on remote working benefits outside of London. More money in people’s pockets in these areas means more money spent in the local economy to drive further investment.

- Resurrect the Council of the North, and allow parliament to sit in York, in a building just across from the train station. Do this for a few years while the Palace of Westminster is being refurbished this decade.

- Properly commit to relocating government offices and agencies to other cities, spreading public sector jobs across the country. This includes the Civil Service, and the Royal Societies. Encourage businesses to follow suit, promoting a more even distribution of economic activity.

The fundamental structure and design of British cities is a key determinant of the country’s overall economic performance. Anything and everything we do is built upon what we do to heal the rift in regional productivity over the next few decades. Shifting this fundamental paradigm is a long-term endeavour whose benefits accumulate slowly but compound dramatically. What we desperately need is momentum generated from this being done properly.

A big part of this is persuading those in charge that meaningful action is urgently required. Fixing regional inequality is nothing new, but sometimes it’s often the most mundane ideas that are the most transformative.

The narrative that success is synonymous with London has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, relegating other cities to the sidelines. But the richness of innovation, the resilience of industries, and the vibrancy of culture should not be monopolised by one city. Regional inequalities were once low in this country, and there’s every reason to strive towards that goal with hope again.